One of the many residents of Somersworth, New Hampshire who served in the American Revolution was Cato Wallingford. Private Cato Wallingford appears in several places on the muster rolls of Captain Joseph Carr’s Company of the 2nd New Hampshire Regiment between 1778 and 1782. Cato Wallingford’s name is also included in a town document dated July 3, 1781 which names men who enlisted for the town of Somersworth for three years and “returned from the army last March during the war.”

What none of these records mention is that Cato Wallingford was Black, and that he was enslaved.

Colonial militias at the beginning of the Revolution often included Black soldiers: Peter Salem and Salem Poor both fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill. But the leadership of the Continental army resisted including Blacks, either free or enslaved, in the Continental army, at least at first. The British army had no such qualms: Virginia royal Governor Dunmore encouraged the slaves of Patriots to run away and join his Ethiopian Brigade of some 800 men. But by the end of 1775, the dire need for additional troops persuaded General Washington to change his mind and the Continental army began accepting Black soldiers into the ranks.

Colonial militias at the beginning of the Revolution often included Black soldiers: Peter Salem and Salem Poor both fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill. But the leadership of the Continental army resisted including Blacks, either free or enslaved, in the Continental army, at least at first. The British army had no such qualms: Virginia royal Governor Dunmore encouraged the slaves of Patriots to run away and join his Ethiopian Brigade of some 800 men. But by the end of 1775, the dire need for additional troops persuaded General Washington to change his mind and the Continental army began accepting Black soldiers into the ranks.

What do we know about Cato Wallingford? When Colonel Thomas Wallingford, one of the richest men in colonial New Hampshire, died in 1771, his extensive estate included four enslaved people: “a Negro man Richmond, a Negro boy Cato, a Negro woman Phillis, and a Negro girl Dinah,” probably living at his primary residence in the Sligo area of old Somersworth (now Rollinsford). It is possible that Richmond and Phillis were Cato’s parents and Dinah his sister, but this is entirely conjectural. Colonel Wallingford’s heirs squabbled over the distribution of his property, including the enslaved people – Phillis died before the estate was settled, and Dinah was described as “disordered in mind & body” – but it seems that Cato at least remained on the property on Sligo with Colonel Wallingford’s widow Elizabeth (often referred to as Madam Wallingford).

Over 600 Black soldiers enlisted in New Hampshire regiments during the American Revolution, and it is estimated that from five to eight thousand Black soldiers served the patriot cause. Their service, along with that of Cato Wallingford, should not be forgotten.

Since Cato was described as a boy in 1771, he was probably in his late teens or early twenties when he enlisted in the army around 1778. In New Hampshire, enlistment bounties for enslaved men who joined the army were given to their owners. Cato’s status while in the army is unclear: was he free when he enlisted, or was he still considered the property of Madam Wallingford? A clue can be found in the Somersworth town records. In April 1782 the town of Somersworth appointed a committee to negotiate with Madam Wallingford respecting Cato. Ultimately the town paid Madam Wallingford a bounty of $15, presumably as recompense for Cato’s service and thereby ensuring his freedom.

And what became of Cato after the war? He seems not to have returned to live in Somersworth, at least not for long. On February 26, 1784, he married Margaret Peterson in Exeter, NH. The following month, the Exeter town constable was ordered to warn several transients to leave Exeter and return to their legal place of residence. The list of these transients included Cato Wallingford, who apparently had been living in Exeter for ten months.

By 1790, Cato was living in Gilmanton, NH. In the census taken that year, Cato and one other person (presumably his wife Margaret) were enumerated under the category “all other free persons” which covered free people of color. The census for Gilmanton counted a total of 22 people who fell under that category (along with one enslaved person) so perhaps there was a small community of free people of color in Gilmanton at the time.

By 1790, Cato was living in Gilmanton, NH. In the census taken that year, Cato and one other person (presumably his wife Margaret) were enumerated under the category “all other free persons” which covered free people of color. The census for Gilmanton counted a total of 22 people who fell under that category (along with one enslaved person) so perhaps there was a small community of free people of color in Gilmanton at the time.

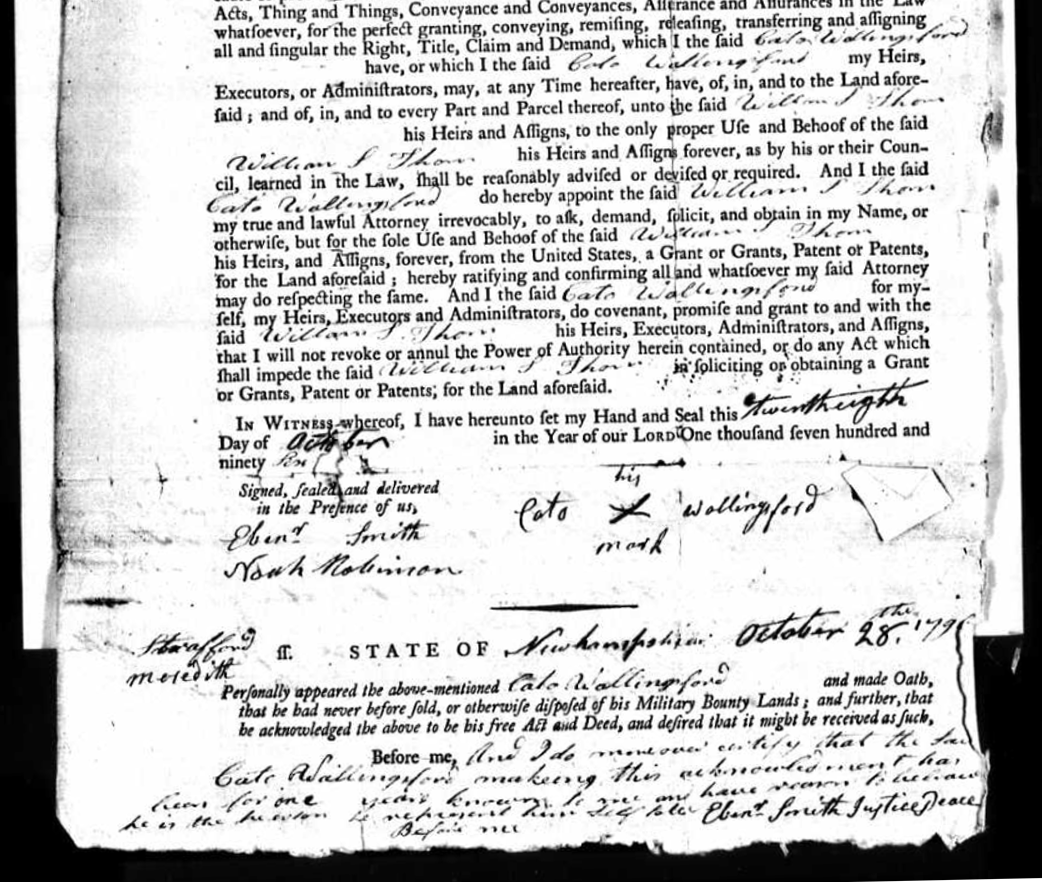

Based on a land transfer document dated October 28, 1791, it seems that Cato may have moved to Meredith the year following the census. Veterans of the Revolution were eligible to receive military bounty land grants in Ohio, and in October 1791 “Cato Wallingford of Meredith” sold his land grant of 100 acres to William Thom, a Philadelphia merchant, for the sum of $20. Unable to read or write, Cato signed the document with his mark (an X). Here the trail grows cold, and we can find no further trace of Cato in either census records or birth and death records.

Over 600 Black soldiers enlisted in New Hampshire regiments during the American Revolution, and it is estimated that from five to eight thousand Black soldiers served the patriot cause. Their service, along with that of Cato Wallingford, should not be forgotten.